Understanding why surgical outcomes vary—and what you can do to prepare your nervous system for the stress ahead

If you have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) or Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), you’ve probably heard conflicting messages about surgery. Some doctors seem worried. Others dismiss your concerns. You’ve read stories online that range from catastrophic to surprisingly uneventful.

Here’s what most conversations miss: anesthesia itself is rarely the problem. The real issue is that surgery acts as a neurologic stress test—and the outcome depends on how much reserve your nervous system has available at the moment it’s tested.

Key Takeaways

- Surgery is a stress test—outcomes depend on your nervous system’s capacity to absorb that stress, not just which drugs are used

- EDS creates mechanical bottlenecks (tissue fragility, joint instability, airway concerns) that reduce your margin for error

- POTS limits autonomic reserve—your body’s “autopilot” system is already working harder than normal before surgery begins

- When both conditions co-exist, risks multiply rather than simply add together

- Good outcomes are achievable when your medical team understands your specific vulnerabilities ahead of time

The Stress Test Framework: Why “Reserve” Matters

Every patient who undergoes surgery faces the same basic sequence: stressor → physiologic response → recovery. Anesthesia introduces vasodilation, altered autonomic tone, airway manipulation, and metabolic stress. Most patients tolerate this because they have sufficient neurologic and autonomic reserve—spare capacity to absorb the demand.

Think of reserve like a battery. A healthy person might start the day at 100% and use 30-40% just living their normal life. Surgery demands another 40-50%. They still have enough charge left to recover.

With EDS or POTS, you might start the day at 70%—not because you’re weak, but because your body is working harder to do the same basic tasks. The same surgery could push you dangerously close to depleted.

The Clinical Reality

This isn’t about being “fragile.” It’s about physiology. Patients with EDS and POTS often have reduced margin—less buffer between functioning well and being overwhelmed. Understanding where those limits are is the difference between preparation and surprise.

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: How Collagen Abnormalities Create Surgical Bottlenecks

EDS encompasses a group of hereditary connective tissue disorders caused by abnormal collagen—the protein that serves as the structural scaffolding for skin, blood vessels, ligaments, organs, and essentially everything that holds your body together.

When collagen doesn’t function correctly, the clinical implications extend far beyond “flexible joints.” The science goes deeper: defective collagen synthesis and cross-linking affect tissue tensile strength, vascular wall integrity, wound healing capacity, and even how local anesthetics distribute through tissue.

EDS Types and Their Specific Surgical Implications

| Type | Key Features | Primary Surgical Concerns |

|---|---|---|

| Hypermobile (hEDS) | Joint hypermobility, chronic pain, frequent subluxations/dislocations, often co-occurs with POTS and MCAS | Positioning injuries, local anesthetic resistance, autonomic instability, prolonged recovery |

| Classical (cEDS) | Skin hyperextensibility, atrophic scarring, easy bruising, delayed wound healing | Tissue fragility, surgical wound complications, hematoma formation, abnormal scar tissue |

| Vascular (vEDS) | Arterial, intestinal, and uterine fragility; thin translucent skin; characteristic facial features | Life-threatening vascular events, organ rupture risk, requires specialized centers only |

The Four Major EDS Bottlenecks Under Anesthesia

1. Airway and Cervical Spine Instability

During general anesthesia, the airway must be secured—typically requiring head positioning and laryngoscopy. In EDS patients, several anatomical vulnerabilities converge: atlanto-occipital instability, cervical hypermobility, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) laxity, and in some cases craniocervical instability.

Excessive neck extension or aggressive jaw manipulation can provoke subluxation, neurologic symptoms, or post-operative pain that persists long after the surgery itself has healed. OrphanAnesthesia guidelines specifically recommend minimizing neck movement, considering fiberoptic intubation, and using smaller endotracheal tubes to reduce mucosal stress.

Clinical translation: The risk isn’t from anesthesia drugs—it’s from mechanical manipulation of structures that lack normal stability. Careful technique matters more than drug selection.

2. Tissue and Vascular Fragility

Collagen abnormalities render tissues more susceptible to injury from routine medical procedures. IV placement can cause vessel dissection. Blood pressure cuffs can produce significant bruising. Adhesive tape can tear fragile skin. Tourniquets—standard in many orthopedic procedures—have been associated with serious complications in EDS patients.

Research published in the Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases notes that some EDS patients develop “extensive haematoma even by repetitive non-invasive blood pressure measurements.” The authors specifically recommend avoiding central venous catheters and arterial lines whenever possible, and using ultrasound guidance when invasive monitoring is necessary.

3. Local Anesthetic Resistance

A significant subset of hypermobile EDS patients report that local anesthetics like lidocaine don’t work effectively—procedures remain painful despite adequate dosing, or numbness wears off too quickly.

This phenomenon, documented in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine and other publications, isn’t true pharmacologic resistance. The leading hypothesis involves altered connective tissue architecture: abnormal extracellular matrix allows local anesthetics to diffuse away from target nerve fibers more rapidly than in normal tissue, reducing both depth and duration of blockade.

For Practitioners

Consider longer-acting agents, higher concentrations, or adjuvant techniques. Regional and neuraxial blocks may have higher failure rates and carry additional risks related to meningeal fragility and potential Tarlov cysts. A detailed history of prior anesthetic experiences is essential.

4. Postoperative Healing and Recovery

Defective collagen doesn’t just affect the operating room—it extends recovery timelines. EDS patients commonly experience prolonged wound healing, abnormal scar formation, higher rates of surgical site complications, and increased postoperative pain and nausea.

These aren’t “anesthesia side effects.” They’re downstream expressions of connective tissue biology under stress. Planning must account for extended recovery needs.

POTS: When Your Autonomic System Is Already Running Hot

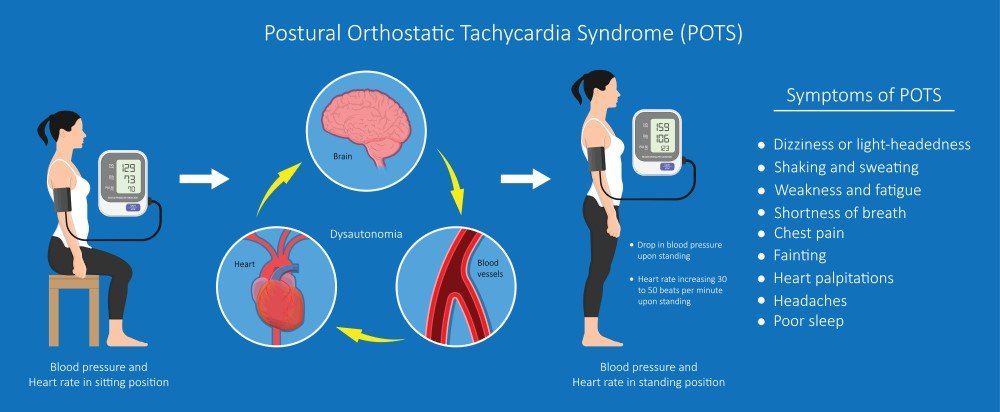

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome represents a form of dysautonomia—dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system that controls heart rate, blood pressure, digestion, temperature regulation, and other “automatic” functions.

The hallmark feature is an excessive heart rate increase (≥30 bpm, or ≥40 bpm in adolescents) within 10 minutes of standing, accompanied by symptoms of orthostatic intolerance—dizziness, lightheadedness, palpitations, fatigue, brain fog, near-syncope.

But here’s what matters for surgery: POTS patients have limited autonomic reserve. Their compensatory mechanisms are already working harder than normal just to maintain baseline function.

The Autonomic Challenge Under Anesthesia

Anesthesia introduces several autonomic stressors simultaneously:

- Vasodilation from anesthetic agents reduces systemic vascular resistance

- Positive-pressure ventilation alters intrathoracic pressure and venous return

- Sympathetic modulation shifts abruptly with induction and throughout the procedure

- Blood loss and fluid shifts challenge volume homeostasis

In a healthy patient, autonomic reflexes smoothly compensate for these perturbations. In POTS, that compensation is already near capacity at baseline.

Research Perspective

A retrospective series of 13 POTS patients undergoing general anesthesia, published in the Journal of Clinical Anesthesia, found that three patients (23%) developed prolonged intraoperative hypotension requiring vasopressor support and aggressive fluid resuscitation. However—and this is crucial—all patients had uneventful postoperative courses when these issues were anticipated and managed proactively.

Perioperative POTS Management Essentials

The literature consistently emphasizes several key strategies:

- Continue POTS medications through the perioperative period—beta-blockers, fludrocortisone, and midodrine serve important hemodynamic functions

- Preoperative volume expansion—crystalloid preloading helps buffer against induction-related hypotension

- Identify personal triggers—heat, dehydration, pain, anxiety, and certain medications can precipitate autonomic crises

- Vigilant hemodynamic monitoring—arterial lines may be indicated for major procedures

- Vasopressor availability—phenylephrine is often first-line due to its selective alpha-1 activity

When EDS and POTS Combine: Multiplicative Risk

EDS and POTS frequently co-occur—particularly hypermobile EDS and POTS, often accompanied by Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS). This triad is increasingly recognized in the literature and presents compounded perioperative challenges.

The risks aren’t additive. They’re interactive:

| EDS Factor | POTS Interaction | Combined Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Fragile blood vessels | Increased fluid requirements | Difficult IV access meets higher volume demands |

| Bleeding tendency | Blood pressure instability | Hemodynamic swings stress fragile vasculature |

| Cervical instability | Autonomic symptom triggers | Neck manipulation can provoke autonomic responses |

| Delayed wound healing | Fatigue and orthostatic intolerance | Extended recovery complicated by inability to mobilize |

| Local anesthetic resistance | Pain as autonomic trigger | Inadequate anesthesia can precipitate POTS flares |

A 2021 case series in Cureus documented the successful perioperative management of patients with combined hEDS and POTS. The authors developed a management flow diagram emphasizing extensive preoperative evaluation, careful positioning, adequate hydration, and extended postoperative observation. Their conclusion: good outcomes are achievable when these factors are proactively addressed.

What You Can Communicate to Your Anesthesia Team

Your goal isn’t to direct the anesthetic plan—it’s to communicate your body’s specific constraints so your team can adapt their approach.

Essential Information to Share

- Your specific EDS type (if known)—vascular EDS requires entirely different precautions than hypermobile EDS

- Cervical spine, jaw, or airway instability—determines airway management approach

- Past experiences with local anesthetics—”numbing shots don’t work well” or “they wear off quickly”

- POTS diagnosis and your typical triggers—heat, dehydration, prolonged standing, specific medications

- Current medications and supplements—many POTS medications should continue through surgery

- Previous surgical experiences—both complications AND successes

- Healing history—slow wound healing, abnormal scars, previous surgical site complications

Frame the conversation as collaboration, not confrontation:

“I have hypermobile EDS and POTS. My main concerns are that local anesthetics don’t work well for me, my neck is unstable, and I have blood pressure drops with position changes. I’ve had good experiences when teams used extra padding, gave me IV fluids before starting, and kept my neck neutral. What other information would help you prepare?”

Preparation Strategies: Building Your Buffer

While you can’t change your underlying connective tissue or autonomic function, you can influence how much reserve you bring into surgery.

Optimize Hydration and Electrolyte Status

For POTS patients especially, adequate intravascular volume is critical. In the days before surgery, ensure you’re meeting your typical fluid and salt intake targets. Dehydration going into a procedure narrows your margin considerably.

Manage Stress Load

Psychological stress draws from the same autonomic reserve as physical stress. Anxiety activates the sympathetic nervous system and can worsen both POTS symptoms and overall stress tolerance. Consider what helps you regulate your nervous system and prioritize those practices pre-operatively.

Stabilize Sleep

Sleep deprivation impairs autonomic function, increases inflammatory markers, and reduces cognitive resilience. Prioritize sleep quality in the week before surgery—this is not the time to push through on inadequate rest.

Document Your Baseline

Know your typical resting heart rate, blood pressure ranges, and orthostatic responses. This gives your medical team a reference point for what’s normal for you, rather than comparing you to population averages that may not apply.

Plan Your Recovery Environment

EDS and POTS patients often need more time and support during recovery. Arrange for help at home, plan for limitations in mobility and energy, and set realistic expectations for your recovery timeline. Rushing recovery depletes reserve faster than it can rebuild.

The Gap in Current Care—And What’s Coming

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: despite clear patterns in the medical literature, most preoperative evaluations still focus on drug allergies, previous complications, and standard vital signs.

What rarely gets measured is the thing that actually predicts outcomes: How much stress can this nervous system absorb right now? Where are the specific bottlenecks?

This isn’t a failure of individual clinicians. It’s a limitation of the current model—we have sophisticated ways to measure cardiac output and hepatic function, but we don’t routinely assess neurologic and autonomic reserve.

That gap is closing. New frameworks for understanding surgical risk are emerging—approaches that move beyond diagnosis-based checklists toward individualized assessment of stress capacity. The goal isn’t to eliminate risk, but to identify where the system is vulnerable and prepare accordingly.

Coming Soon

A new framework for understanding neurologic reserve and surgical preparation is launching soon. If you want to be notified when it’s available—and learn how to assess your own stress capacity before your next procedure—join the waitlist.

The Bottom Line

If you have EDS, POTS, or both, surgery doesn’t have to be terrifying. But it does require preparation that goes beyond the standard checklist.

The science is clear: these conditions change how your body responds to anesthesia and surgical stress—not randomly, but in predictable, manageable ways. Tissue fragility, joint instability, autonomic dysregulation, and altered pharmacology all create specific bottlenecks that can be anticipated and addressed.

Your job isn’t to become a medical expert. It’s to help your team understand the specific operating system they’re working with. That information—communicated clearly and collaboratively—is the bridge between a stressful unknown and a well-prepared success.

Preparation must be individualized.

Understanding must come before reassurance.

Measurement must come before intervention.

Medical Disclaimer: This article is educational and does not constitute medical advice. Individual responses to surgery and anesthesia vary based on many factors. Always consult with your healthcare team about your specific situation. The information provided should inform—not direct—clinical decision-making.

About the Author

Sande Bargeron, PA-C, CAA, PhD is a Certified Anesthesiologist Assistant and brain health optimization expert with decades of experience in perioperative medicine. Her work focuses on understanding why some patients struggle with surgical stress and recovery while others sail through—and what can be done to close that gap.

With a unique perspective spanning clinical anesthesia practice, neuroscience research, and patient advocacy, she helps patients prepare their brains and bodies for the stress of surgery—and life.