MTHFR is only the beginning. The methylation genes no one is talking about could be the missing piece of your surgical recovery puzzle.

If you have heard of MTHFR, you probably think of it as the gene that matters for health. Maybe you learned you carry a variant and were told to take methylated B-vitamins. Maybe someone mentioned it in the context of detoxification. And if you are facing surgery, you may have wondered: does this affect how I recover from anesthesia?

The answer is yes. But here is what almost no one tells you: MTHFR is only one worker on a much bigger assembly line.

Your body relies on an entire network of methylation genes to detoxify anesthetic drugs, repair DNA after surgical stress, build neurotransmitters, control inflammation, and deliver oxygen to healing tissues. If any part of that network is compromised, your brain and body have less capacity to recover. Not because the surgery went wrong — but because the system was already running low before you went in.

The core question is not: “Is my MTHFR gene normal?”

The real question is: “Does my entire methylation system have enough reserve to handle the stress of surgery?”

What Is Methylation — and Why Does Surgery Demand So Much of It?

Methylation is a biochemical process that happens billions of times per second in your body. At its simplest, it involves transferring a tiny chemical tag — a methyl group (one carbon atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms, written as CH₃) — from one molecule to another. That transfer acts like a molecular instruction, telling cells what to do and when to do it.

Think of methylation as your body’s internal messaging system. It does not just do one thing — it coordinates many critical operations simultaneously:

- Detoxification: Clearing anesthetic drugs, metabolic waste, and inflammatory byproducts through your liver’s Phase II conjugation pathways

- DNA repair: Fixing cellular damage caused by oxidative stress during surgery

- Neurotransmitter synthesis: Building serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine — the chemicals your brain needs to think clearly, regulate mood, and manage pain

- Inflammation control: Regulating the expression of inflammatory genes like TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β that surge during and after surgery

- Homocysteine recycling: Converting this potentially toxic amino acid back into methionine, a building block your body needs for hundreds of reactions

Under normal conditions, your methylation system handles all of this quietly in the background. But surgery is not a normal condition. It is one of the most intense physiological stresses your body can experience.

What the Research Shows

A 2024 study in the Journal of Thoracic Disease found that general anesthesia induces rapid, acute changes in cell-free DNA methylation — detectable within one hour of anesthesia administration. An earlier study found that global DNA methylation levels declined by 26% during major surgery under opioid-based general anesthesia, with simultaneous drops in DNMT1a expression of 68%, DNMT3a of 65%, and DNMT3b of 71%.

Liang W, et al. J Thorac Dis. 2024;16(11):7592-7606. • Garré JM, et al. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:727085.

When surgery demands massive amounts of methylation capacity — for detox, for DNA repair, for inflammation control — and your system is already compromised by genetic variants, your body has to make choices about which processes to prioritize. Neurotransmitter synthesis may get cut. DNA repair may be delayed. Inflammation may run unchecked longer than it should. The result? Slower cognitive recovery. Longer brain fog. More vulnerability to the neurological effects of surgical stress.

MTHFR: The Gene Everyone Knows (and Why It Is Not the Whole Story)

MTHFR (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase) is the most widely recognized methylation gene, and for good reason. It controls the first critical step in the methylation cycle: converting dietary folate (vitamin B9) into its active, usable form called 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF). Without this conversion, the entire downstream methylation process slows down.

The MTHFR C677T variant is one of the most common genetic polymorphisms in the world. In some populations, the heterozygous form (one copy of the variant) affects 30–40% of people, while the homozygous form (two copies) affects 10–15%. The homozygous C677T variant can reduce MTHFR enzyme activity by up to 70%, creating a significant bottleneck in the methylation pathway.

Think of MTHFR as the worker at the front of the assembly line — the one who receives raw materials (folate) and prepares them for the rest of the line. If that worker slows down, everything downstream gets backed up. But that worker is not the only one on the line. And if other workers further down the line are also struggling, the slowdown compounds.

MTHFR and Anesthesia: The Nitrous Oxide Problem

One of the most clinically significant interactions between MTHFR and anesthesia involves nitrous oxide (N₂O) — commonly known as “laughing gas.” Nitrous oxide irreversibly oxidizes vitamin B12, preventing it from functioning as a cofactor for methionine synthase. This effectively shuts down the B12-dependent pathway for recycling homocysteine to methionine.

For a person with normal methylation, this is a temporary inconvenience the body can work around. For someone with an MTHFR variant, it creates what researchers have called a “double hit” — both the folate pathway (already compromised by MTHFR) and the B12 pathway (inactivated by nitrous oxide) are impaired simultaneously.

Clinical Evidence

A study published in Anesthesiology (2008) found that patients with MTHFR mutations developed significantly higher plasma homocysteine concentrations after nitrous oxide anesthesia than those without the mutation, and this elevation was associated with increased postoperative myocardial ischemia. A case report published in the New England Journal of Medicine described severe neurological deterioration and death in a child with MTHFR deficiency after two exposures to nitrous oxide, demonstrating the potential severity of this interaction. A 2017 study in Turkish Journal of Anaesthesiology and Reanimation evaluating 12 pediatric patients with MTHFR deficiency confirmed that while sevoflurane and propofol appeared safe, nitrous oxide was to be strictly avoided.

Nagele P, et al. Anesthesiology. 2008;109(1):36-43. • Selzer RR, et al. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(1):45-50. • Sari S, et al. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim. 2017;45(4):220-225.

Critical Takeaway: If you carry an MTHFR variant and are scheduled for a procedure that may involve nitrous oxide — including dental procedures — discuss this with your provider. Nitrous oxide-free anesthetic alternatives exist and are considered safe for patients with methylation gene variants.

Beyond MTHFR: The Methylation Genes No One Is Talking About

Here is where the conversation needs to expand. MTHFR is the most familiar name, but your methylation system depends on a team of enzymes, each encoded by its own gene. If any team member underperforms, the whole system feels it.

MTR (Methionine Synthase): The Homocysteine Recycler

MTR encodes the enzyme methionine synthase, which performs a critical job: converting homocysteine back into methionine, using methylated folate (provided by MTHFR) and vitamin B12 as essential partners. This is the step where the folate cycle and the methionine cycle meet — the crossroads of your methylation system.

The MTR A2756G variant can alter the enzyme’s activity, affecting how efficiently it processes homocysteine. When MTR underperforms, homocysteine accumulates — a recognized independent risk factor for cardiovascular complications and cognitive impairment, both of which are amplified in the surgical setting.

MTRR (Methionine Synthase Reductase): The B12 Recycler

MTRR keeps methionine synthase (MTR) working. Over time, the B12 cofactor that MTR depends on becomes oxidized and inactive. MTRR reactivates it. Without functional MTRR, MTR grinds to a halt — even if the enzyme itself is perfectly normal.

The MTRR A66G variant is common and consequential: it can result in up to three-fold lower enzymatic activity and a four-fold higher homocysteine-to-methionine ratio at the cellular level. When combined with MTHFR variants, the compounded effect on methylation capacity is significant.

Compounding Effect

Research published in the American Journal of Medical Genetics found that the combination of MTR 2756AG and MTRR 66AG (double heterozygosity) was a significant independent risk factor for elevated homocysteine, with an odds ratio of 5.0 — meaning the combined effect was far greater than either variant alone.

Bosco P, et al. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;121A(3):219-224.

DNMTs (DNA Methyltransferases): The Gene Expression Controllers

DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b are the enzymes that physically add methyl groups to DNA, controlling which genes are turned on and off. This process — called epigenetic regulation — is how your body manages inflammation, directs tissue repair, and maintains neuronal function after stress.

This is where the connection to anesthesia becomes profound. Research shows that anesthetics directly alter DNMT activity. Under general anesthesia, DNMT expression can drop dramatically, leading to widespread changes in DNA methylation patterns. In the developing and aging brain — where resilience is already lower — these changes can have lasting consequences.

Anesthesia and Epigenetic Disruption

A comprehensive 2025 review in PMC found that anesthetics including propofol, isoflurane, and sevoflurane can trigger both transient and persistent epigenetic modifications through altered DNMT activity, with effects including hypomethylation of inflammatory genes (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) enhancing neuroinflammation, hypermethylation of BDNF promoters leading to reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression (critical for memory and learning), and disrupted histone acetylation patterns in the hippocampus, correlating with memory impairment. The review noted that pediatric and elderly patients show heightened susceptibility due to brain plasticity in the young and diminished resilience in the old.

PMC. Anesthetic-induced epigenetic alterations: mechanisms and long-term clinical implications. 2025. • Hepp T, et al. Cells. 2022;11(19):2954.

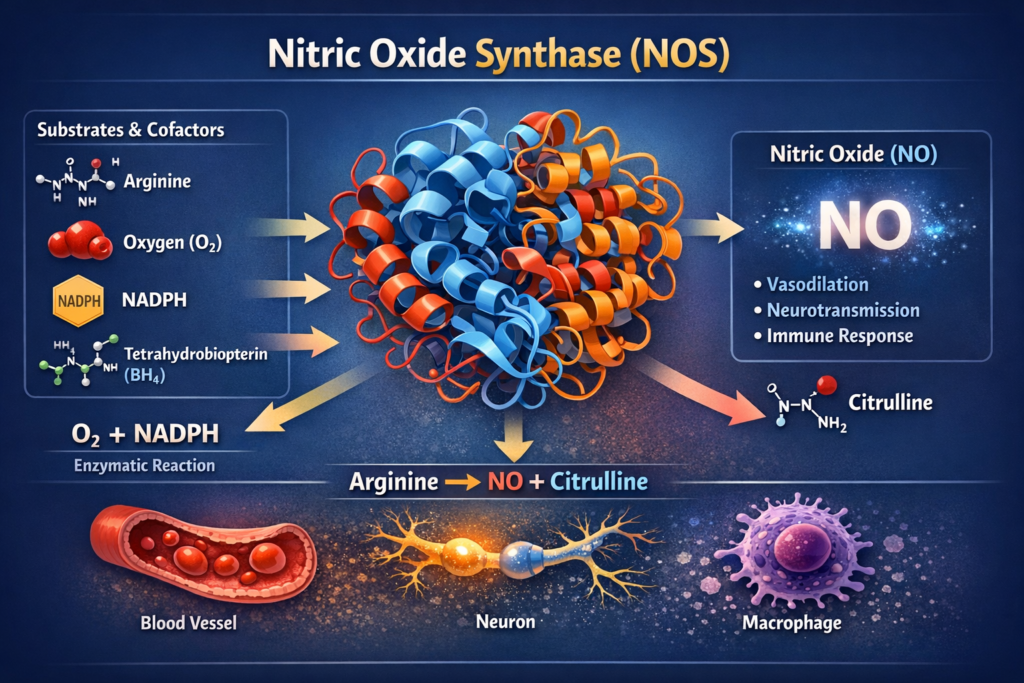

NOS (Nitric Oxide Synthase): The Blood Flow Regulator

Nitric oxide (NO) is a tiny molecule with an enormous job: it dilates blood vessels, ensuring oxygen and nutrients reach your brain and healing tissues. The NOS genes (particularly eNOS/NOS3 and nNOS/NOS1) encode the enzymes that produce nitric oxide.

Variants in NOS genes can reduce nitric oxide production, which means less blood flow to the brain and surgical sites during the exact moment your body needs it most. After the stress of anesthesia, when your brain is trying to recover, reduced cerebral blood flow can prolong cognitive fog and slow tissue healing.

NOS Variants and Cerebral Blood Flow

A study published in the Journal of Neurotrauma found that variants of the NOS3 gene significantly affected cerebral blood flow after brain injury. Patients with the normal T/T genotype at the −786T>C location maintained average cerebral blood flow of 57.7 mL/100g/min, while those with the C/C genotype dropped to 37.3 mL/100g/min — a 35% reduction. Both patients who were homozygous C/C died within 6 months, compared to a 17–20% mortality rate in other genotypes.

Robertson CS, et al. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28(5):727-740.

Nitric oxide is also critical for wound healing. Research shows that iNOS-knockout mice demonstrated delayed wound closure and decreased collagen deposition, while supplementation with arginine (an NO precursor) improved wound healing in normal animal models. For surgical patients, this means NOS gene variants could affect not just brain recovery but the physical healing of the surgical site.

The Bigger Picture: How Methylation Bottlenecks Compound Under Surgical Stress

Here is the concept that changes everything: these genes do not work in isolation. They form an interconnected network, and a variant in any one of them creates a bottleneck that affects the entire system.

Imagine a highway system where MTHFR controls the on-ramp, MTR and MTRR manage a critical interchange, DNMTs direct traffic to different neighborhoods, and NOS controls how wide the roads are. If the on-ramp is narrowed (MTHFR variant), traffic slows throughout the system. But if the interchange is also backed up (MTR/MTRR variants), and the roads themselves are narrowed (NOS variants), and the traffic controllers are not keeping up (DNMT disruption from anesthesia) — you get gridlock.

Under normal daily conditions, your body may compensate for one or even two of these bottlenecks. You might not even know they exist. But surgery removes the margin for compensation. It floods the system with demand — demand for detoxification, for DNA repair, for inflammation control, for neurotransmitter synthesis — all at once. And every bottleneck that was invisible before becomes visible in the recovery room.

This Is What Neurologic Reserve Actually Means

Your brain’s neurologic reserve is its built-up capacity to handle stress without breaking down. Methylation is one of the key systems that builds and maintains that reserve. When methylation pathways are compromised — by genetic variants, by nutritional deficiencies, by hormonal shifts like perimenopause, by chronic stress — your reserve is lower before you ever reach the operating room.

Surgery does not create the vulnerability. It reveals what was already running low.

The question is not whether surgery will stress your system — it will. The question is whether your system has enough reserve to handle that stress and recover. That is measurable. And if it is measurable, it is buildable.

Who Needs to Pay the Most Attention?

While methylation gene variants affect people across all demographics, certain populations carry compounded risk when facing surgery:

Neurodivergent Individuals

A growing body of research links neurodivergent conditions — including ADHD and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) — to differences in DNA methylation patterns. A 2025 review in PMC found abnormal methylation in key regulatory genes like MECP2 and SHANK3 in ASD, while large epigenome-wide studies have identified differentially methylated positions associated with ADHD. These methylation differences suggest that some neurodivergent individuals may have pre-existing variations in the very pathways that surgery relies on most heavily for recovery.

This does not mean neurodivergent individuals cannot recover well from surgery — it means their methylation capacity may need more intentional support before, during, and after the procedure.

Women in Perimenopause and Menopause

Declining estrogen levels during perimenopause place extraordinary additional demands on the methylation system. Estrogen is metabolized through methylation-dependent pathways (COMT), and as hormones fluctuate wildly during the transition, methylation demand increases at the very time the system’s cofactors may be depleted. Research has shown that MTHFR mutations are more strongly correlated with depression in postmenopausal women — a marker suggesting methylation challenges become clinically significant as hormonal demands on the pathway increase.

Add surgical stress to a perimenopausal methylation system, and the compounding effect can be substantial. (For a deep dive into this interaction, see our companion article: Perimenopause and Anesthesia Recovery: Why Your Brain Deserves Better Preparation.)

Older Adults

Aging is associated with global changes in DNA methylation — sometimes called “epigenetic drift” — that reduce the precision of gene expression regulation. Combined with age-related declines in B-vitamin absorption, reduced hepatic blood flow (approximately 1% per year after age 40), and diminished antioxidant capacity, older adults often enter surgery with lower methylation reserve. This helps explain why postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) and delirium disproportionately affect older surgical patients.

Evidence-Based Strategies to Support Your Methylation System Before Surgery

The most powerful insight from the methylation research is this: these are not fixed vulnerabilities. While you cannot change your genes, you can support the system that those genes operate within. The following strategies are drawn from the clinical evidence base — but should always be discussed with your healthcare team before implementation, particularly in the surgical context where some supplements may need to be timed or paused.

Step 1: Know Your Methylation Gene Status

Consider genetic testing for key methylation variants — not just MTHFR, but also MTR, MTRR, COMT, and if possible, NOS variants. Discuss results with a practitioner who understands functional genomics. A simple genomic panel can reveal bottlenecks that have been silently affecting your recovery capacity for years.

Step 2: Support Methylation Cofactors

The methylation cycle depends on specific nutrient cofactors. If you carry known variants, work with your provider to consider:

- Methylated folate (L-methylfolate/5-MTHF): Bypasses the MTHFR bottleneck directly

- Methylcobalamin (methylated B12): Provides the active form of B12 needed by MTR for homocysteine recycling

- P-5-P (pyridoxal-5-phosphate, active B6): Required for the transsulfuration pathway that converts homocysteine to cysteine and eventually glutathione

- Riboflavin (B2): An essential cofactor for MTHFR enzyme function that is frequently overlooked

- Magnesium: Required for over 300 enzymatic reactions, including multiple steps in the methylation cycle

Step 3: Optimize Dietary Methylation Support

Food is foundational. Prioritize:

- Folate-rich foods: Dark leafy greens, asparagus, avocado, legumes, beets

- Choline sources: Eggs (especially yolks), liver, cruciferous vegetables — choline provides an alternative methylation pathway through betaine

- B12-rich foods: Animal proteins, liver, wild-caught fish, nutritional yeast for vegetarians

- Sulfur-rich foods: Garlic, onions, cruciferous vegetables — support glutathione production and Phase II detoxification

Step 4: Communicate with Your Anesthesia Team

This is where knowledge becomes protective action. Before your procedure:

- Share your MTHFR/methylation gene status with your anesthesiologist

- Discuss avoiding nitrous oxide if you carry MTHFR, MTR, or MTRR variants

- Ask about anesthetic agents that minimize methylation disruption — sevoflurane and propofol (TIVA) are generally considered safer alternatives for patients with methylation variants

- Request monitoring if you have known elevated homocysteine levels

Step 5: Support Antioxidant and Detoxification Capacity

Methylation and antioxidant systems are deeply intertwined — the methylation cycle feeds into glutathione production, your body’s master antioxidant. Strategies include:

- N-acetylcysteine (NAC): A direct glutathione precursor

- Reduce liver burden: Minimize alcohol, processed foods, and unnecessary medications in the weeks before surgery

- Adequate hydration: Supports both detoxification and blood flow

- Sleep optimization: Sleep is when DNA repair peaks — prioritize circadian rhythm stability before surgery

Important: Always discuss supplements with your surgical team, as some may need to be discontinued before surgery.

The Paradigm Shift: From “Cleared for Surgery” to “Ready for Surgery”

The current surgical clearance model asks one question: “Is there a reason to cancel this surgery?” It checks your heart. It checks your lungs. It checks your labs. It clears you to proceed.

But it does not ask: “Is your brain ready to handle this stress?”

It does not measure your methylation capacity. It does not assess whether your homocysteine recycling can keep up with surgical demand. It does not evaluate whether your DNMT enzymes have enough substrate to manage the epigenetic storm of anesthesia. It does not check whether your NOS system can deliver adequate blood flow during recovery.

These are not theoretical concerns. They are measurable, modifiable, and deeply connected to how you recover.

Being cleared for surgery is not the same as being prepared for surgery.

Clearance tells you the procedure is safe to perform. Preparation means your body and brain have the reserve to recover well. Methylation is one of the foundations of that reserve — and it is within your power to support it.

Something New Is Coming

What if there were a way to measure your brain’s resilience before surgery — to see the bottlenecks, identify the vulnerabilities, and take action before the stress reveals what was already running low?

That question is exactly what we have been building toward at Beyond Brain Health. Stay tuned — because measuring reserve is about to change the conversation about surgical preparation.

Follow Beyond Brain Health for the next step in this journey.

Disclaimer: This information is for educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Always consult with your healthcare team before making changes to your surgical preparation plan. Some supplements may need to be discontinued before surgery — discuss timing with your provider. Genetic test results should be interpreted by a qualified practitioner familiar with methylation biochemistry and pharmacogenomics.

About the Author

Sande Bargeron, PA-C, CAA, PhD is a brain health optimization expert and neuro-resilience specialist. With decades of experience in anesthesia and a commitment to translating complex neuroscience into actionable clinical strategies, she helps patients and practitioners understand how the brain responds to surgical stress — and what can be done, before the surgery, to build lasting neurologic resilience. Her work bridges the gap between clinical research and practical preparation, giving patients the knowledge to become active partners in their own recovery.